The (Nearly) Lost Art of Catching Rain

Photo Above: The author’s 600-gallon rainwater cistern, tucked away in the boat shed. It provides all water needed outdoors at his home in central Virginia.

__________________

With Cities Facing Critical Water Shortages, Perhaps It’s Time to Revisit An Ancient Water Supply System?

Human societies have been harvesting rain for their water supply for thousands of years.The construction and use of cisterns to store rainwater can be traced back to the Neolithic Age, more than 7,000 years ago, when waterproof lime plaster cisterns were built in the floors of houses in villages of the Levant (Southwest Asia).

One of my favorite examples of rainwater harvesting can be found in the sprawling maze of courtyard areas in Venice (see map below). Huge bowl-shaped basins were hand dug hundreds of years ago beneath these Venetian courtyards and then filled with sand, serving as a natural filter to cleanse the rainwater as it collected in the basin. The plazas were then surfaced with paving stones to direct runoff into perforated pavers, into which the rainwater could percolate and fill up the sand basins (see cross-section diagram below). In the center of these runoff-collecting plazas, an ornate, sculptured well head (photo below) would provide access to an open shaft, from which water could be extracted with buckets for drinking and other household uses.

Ancient Venetians were very serious about harvesting the rain. The red dots represent thousands of individual courtyards where water was collected in sand-filled underground basins and used for domestic purposes. (From Ursino and Pozzato 2019)

The construction of the Venetian cisterns involved digging a huge basin — 3-4 meters in depth — that would be filled with sand. A layer of paving stones was laid at the surface, sloping so as to direct runoff into perforated pavers where water could percolate into the basin. The water was then extracted for domestic use from a well constructed in the center of the plaza.

Example of an ornate, sculptured Venetian well head (left) and a courtyard plaza with well head (right). Photos by Brian Richter

Revisiting an Ancient Water Supply

One of the unfortunate consequences of modern water distribution systems, such as the underground network of pipes and pumps that deliver water to your home, has been a near-complete disappearance of the use of cisterns in cities. Once we became able to access abundant water simply by turning on a tap, cisterns quickly disappeared from the urban landscape.

Tragically, we now use highly-treated potable drinking water to irrigate our lawns and gardens!

But many cities today are facing extreme challenges in providing sufficient drinking water supplies to their citizens, particularly in areas where populations are growing rapidly, or traditional water supplies — such as rivers and aquifers — are being over-tapped and depleted.

Perhaps it is time to revisit the opportunity to catch water falling from the sky for our use outdoors?

Using Rainwater to Irrigate Outdoor Landscapes

During the past few years, my research group has been assessing the implementation of urban water conservation strategies in many cities across the US. One thing has become quite obvious to us: virtually all successful water conservation programs have placed heavy emphasis on reducing outdoor water use.

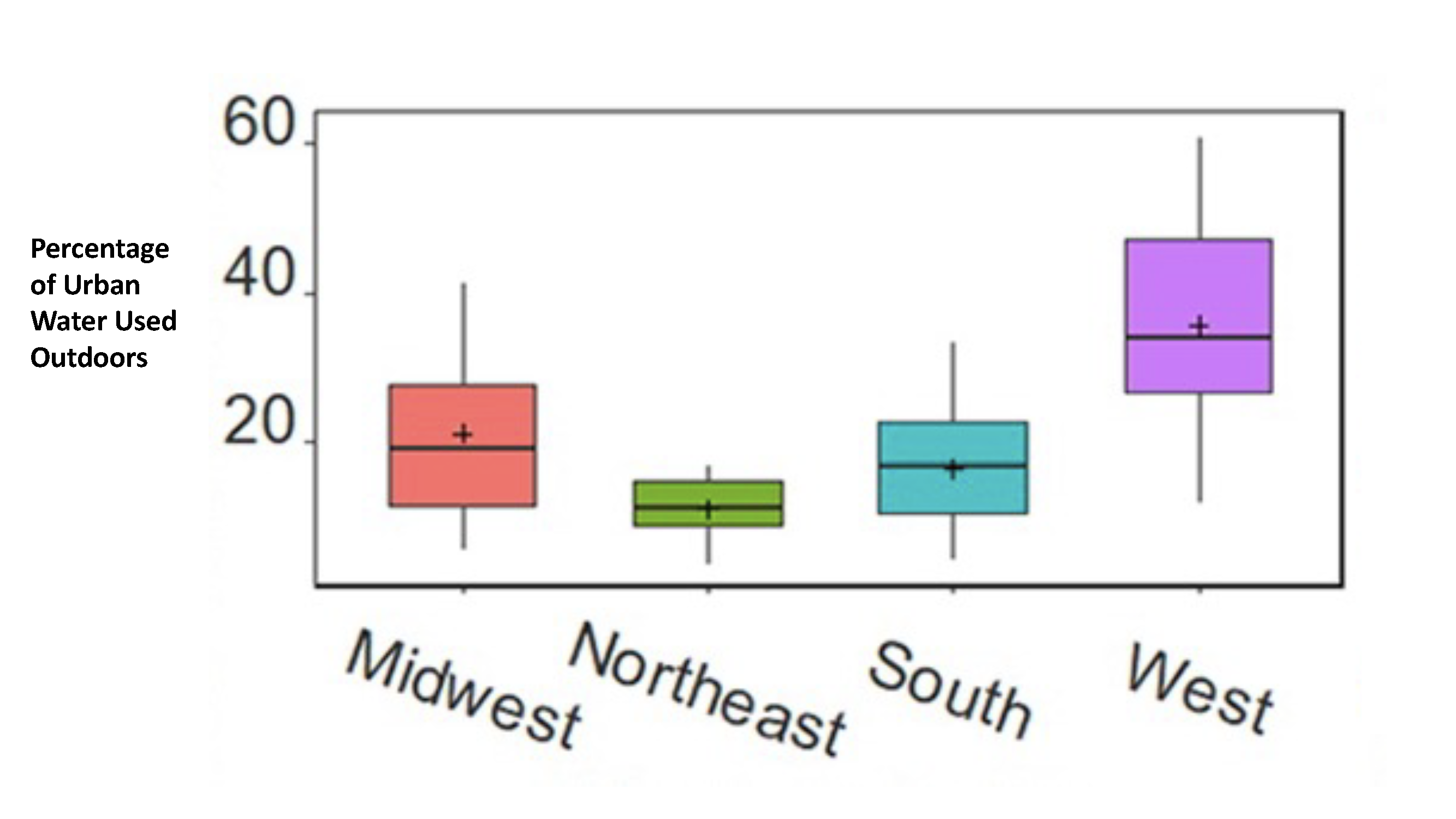

Focusing on outdoor water use makes a great deal of sense in a water conservation program because outdoor use commonly accounts for a large portion of total water use in cities. An excellent recent analysis of 126 cities by researchers at Colorado State University documented that outdoor water use varies greatly across the United States, but can exceed 60% of total urban water use in the warmer, drier western states.

The percentage of total water use that is used for outdoor landscape and garden watering varies across the US, but can exceed 60% in some western cities. In each region, the horizontal lines inside the boxes indicate the median (50%) value, the upper and lower tips of the vertical lines represent the highest and lowest values. (From Chinnasamy and others 2021).

The percentage of total water use that is used for outdoor landscape and garden watering varies across the US, but can exceed 60% in some western cities. In each region, the horizontal lines inside the boxes indicate the median (50%) value, the upper and lower tips of the vertical lines represent the highest and lowest values. (From Chinnasamy and others 2021).

Most of the cities we’ve reviewed have implemented outdoor water conservation by financially incentivizing the conversion of water-guzzling lawns and other thirsty vegetation with water frugal landscapes, such as by planting native or drought-tolerant grasses and shrubs. For example, the city of Las Vegas, Nevada pays homeowners $3 per square foot to rip out their grass lawns and replant with vegetation requiring much less water. The city’s “Cash for Grass” program has reduced residential drinking water use by an astonishing 19-21%.

A homeowner’s choice of landscape vegetation matters a great deal to outdoor water use. Water-guzzling landscape areas such as grass lawns (left) can be very water consumptive, as compared to native or drought-tolerant plants (right).

A homeowner’s choice of what to plant outdoors is very important in water use. However, opportunities to use captured rainwater — instead of potable drinking water supplies — to irrigate landscape areas is too often overlooked in urban water conservation programs.

Imagine how much potable drinking water could be saved in cities if all homeowners and businesses were capturing all their needed outdoor water from their rooftops!

In my own personal experience, the process of uncoupling my outdoor watering from my drinking water system was very easy, and affordable. In addition to the rainwater tank pictured at the top of this blog, I installed a small water pump so that I could create enough pressure in my system to push my captured rainwater through a drip irrigation system or sprinklers.

Legal Limitations on Rainwater Harvesting

I have been asked many times whether it is legal to capture rainwater. The good news is that it is legal in all US states. Unfortunately, however, two states — Utah and Colorado — severely limit how much rainwater can be captured.

In Utah, a homeowner is allowed to install cisterns holding a maximum of 2,500 gallons, which is oftentimes insufficient to meet all outdoor watering needs. But Colorado’s limitations are far more severe. The state limits homeowners to just TWO 55-GALLON RAIN BARRELS (110 gallons total)! This policy may be well-intentioned (i.e., to protect the state’s water rights system), but it’s irrational. It does not make any sense for the state to limit homeowners in their rainwater capture while placing no restrictions on groundwater pumping for domestic use. Consider too the enormous financial costs of building and maintaining stormwater infrastructure to control the excessive runoff that is produced from urban roofs and pavement areas, and the ecological damage done to urban streams due to excessive runoff. These highly undesirable costs could be substantially reduced if homeowners were encouraged to capture some portion of the accentuated runoff from roofs and paved surfaces.

In contrast, there is a growing number of enlightened and progressive states and cities that actually REQUIRE or at least strongly encourage the use of rainwater harvesting, and many cities are financially subsidizing the purchase of cisterns and associated equipment. In my next blog, I’ll interview some water harvesting experts in Tucson, Arizona to gain additional insights into the benefits of rainwater harvesting and their success in getting homeowners to start catching rain.

Sizing Up Your Outdoor Water Needs

You might be wondering how much rainwater storage you’ll need for your outdoor water use?

Many homeowners become very frustrated after going to the effort to install a rain barrel or two, only to realize that those 55-gallon barrels run out of water very quickly! If you’re serious about water conservation, you’re going to need at least 500 gallons of cistern storage.

When I became interested in harvesting rainwater, I looked online to find a calculator that I could use to estimate the size of the rainwater cistern I would need, but what I found left much to be desired. The available calculators were too complicated to use, and none of them were based on actual water usage at my residence. So I cooked up my own simple, quick-and-dirty calculator to help estimate the needed volume of my cistern, along with estimates of potential water and money savings.

You can download my Rainwater Harvesting Calculator here.

My simple calculator is based on a homeowner’s monthly water bills for the past year.

I hope you’ll give it a try. And as always, drop me a note to let me know what you think!! (brian@sustainablewaters.org or the comments section in this blog)

Hi Brian,

I hope you are doing well. Just like your previous posts, I enjoyed reading this one too. You may know that I am an Iranian-American, and proud of that heritage. I grew up in Tehran until the age of 21 when I left the country for the US. The Tehran that I grew up in was (and to a large extent it still is) a fairly modern and sophisticated city with modern amenities including Western-style city water. Those amenities were harder to find in the rural areas. I have many fond memories of our travels in the countryside. A ubiquitous feature of the smaller towns and villages was the cisterns that people relied upon to obtain their drinking water. Unlike your cistern, these were underground and people had to descend the equivalent of two or three stories to reach their outlets. (Alternatively, hand-operated mechanical pumps were used to bring the water to the ground level.) No matter how dry the area, these cities and villages never ran out of water. My guess is that the systems used were variations of the Venetian system you have described, or vice-versa.

Agricultural needs, on the other hand, were met through the qanat system that relied on aquifers and natural springs. Traveling through the desert areas (to the South and East of Tehran) we were sometimes totally surprised by the presence of thriving green hamlets irrigated by qanats that brought the farmers waters that originated from springs tens of miles away. Their residents rarely complained about water scarcity but always used the water sustainably and responsibly: the opposite of how we use the waters of Colorado River.

As I reminisce about my earlier days, I pick up a hopeful tone in your message: We still have a chance to save our future but only if we learn from the time-honored methods of water conservation developed over thousands of years.

Regards,

Ali